My Path to Dashlane: Hip Hop, Marie Kondo, and the Work That Matters Now

I’m often asked why I joined Dashlane, and my answer may not be what you’re expecting, based on how I normally hear others explain their career moves. There’s the predictable walk through the resume, painting an inexorable progression of previous roles culminating in the new one. Then there’s “I’m joining X because I believe [insert investor pitch here] and [personal story derivative of the founder narrative].” There’s the response favored by more creative types, which essentially boils down to “It’s part of my process.” And there’s the similarly endearing, concise response that successfully forestalls further conversation: “I wanted to join an earlier-stage company and try my hand at a tech pure play.”

The truth is: I’m following my own path. And I’d love for you to come along — especially if you’re following yours too.

Chinese Hip-Hop Crackdown: Discovering My Mission

Mine starts in China, the day a colleague there told me that the government was trying to shut down hip-hop. We’d worked together since the early days of social media, which provided a vital connection to him and to a scene poised to lead global popular culture. Creative culture in China once lagged behind the white-hot nucleus of global energy emanating from Hong Kong and, more recently, Seoul. Over time though, its contemporary art became more vibrant, then fashion — then the nascent Chinese hip-hop scene started to pop. Then, in the wake of a government crackdown over its “decadence,” it fizzled.

This turn of events wasn’t really surprising. Staying connected to friends in China through social media had become more and more difficult as our internets diverged. During home visits with Chinese consumers, they’d tell me about using VPNs to get to the content or social sites they wanted. We used to see our Chinese friends and colleagues online all the time, but eventually they migrated to government-sanctioned — and surveilled — platforms they could access more easily.

For the most part, Western execs working in China get passed through to the sites we’re accustomed to frequenting so we won’t realize how extensively the government curtails locals’ civil liberties. Or worry about how much of our own information is captured. Flying out after my last visit, I waited until I was on the plane to post a photo of my hotel’s convenient notice card listing sites guests might have trouble accessing. The person sitting next to me looked over my shoulder and said, “You really should wait until you’re not over Chinese airspace."

In that moment, the dangers of surveillance technologies in the hands of autocrats became clear and present, and the abstraction of “privacy” urgently began to matter to me. After all, privacy is nothing more than the ability to make our own choices without fear. Day to day, surveillance breeds conformity, which is anathema to creativity. Over time it emboldens and empowers tyranny absolutely.

Marie Kondo Conquers Big Tech: Solving A Real Problem

I took a short break between my time at Patagonia and Sonos to do some tidying up. I’d just read Kondo’s book, and I pegged my start date to the time I thought it would take me to declutter. After leaving Sonos and before starting at Lyft, I did the same thing — only this time, I was tidying up my digital life, which was chaos after several years spent competing with Big Tech in a venture-backed startup racing to go public.

Enter Dashlane, which I downloaded to tame the morass of passwords that bedeviled me. It was a revelation. I used it every day and couldn’t imagine going back to a life without it. It allowed me to easily tack between Safari and Chrome and to quickly set up all my non-native apps on my new Mac. It also helped me glide past the paywalls springing up to herald the otherwise delightful resurgence of journalism and publishing. By quickly becoming indispensable, Dashlane reminded me of early experiences with Spotify and Audible.

But it also reminded me of Facebook Connect (since renamed Login), and why a company that lives off your data can’t truly make a privacy product. What makes Facebook so valuable to marketers — so much more valuable than Google or Spotify, for example? First, it can individually track and target you across your entire digital footprint, even when you’re not logged in. Second, Facebook benefits from powerful network effects, where its scale affords a rich data set to train its AI, which drives more engagement and thus more data.

As one former Facebook marketer put it to me, “It’s so accurate because its data set is basically all of humanity.”

Connect was, in a nutshell, the lynchpin for leveraging your identity at scale. It seemed so harmless, and so helpful, to log in with Facebook across your digital journey. Little did we know that doing so would unlock a Pandora’s box like Cambridge Analytica, Brexit, and Trump. It was incredibly exciting to have a product like Dashlane provide the same utility as Facebook Connect without the ulterior motives of monetizing my activities in order to manipulate my behavior.

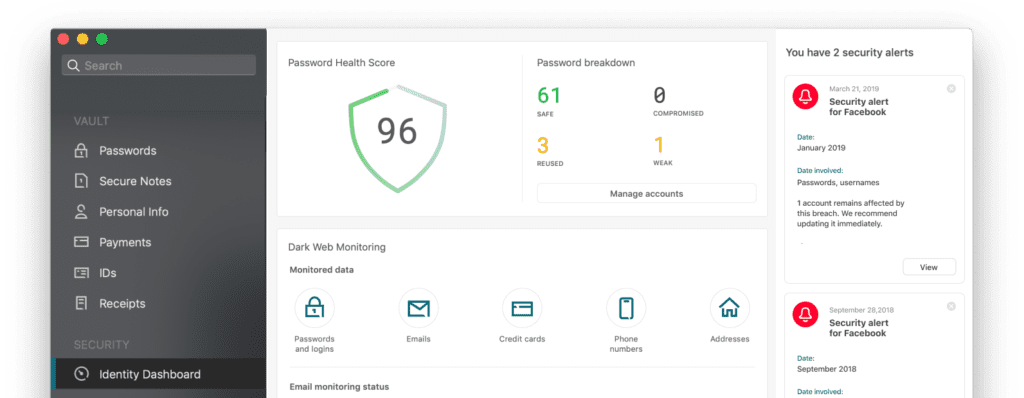

A few months later, Dashlane surprised me with my first alert. My identity had been compromised by a Facebook data breach. Dashlane showed me exactly which accounts had been breached, which passwords to reset, and gave me one button to do it. They weren’t manipulating me; they were looking out for me. I was sold.

Crisis of Consciousness: Doing the Work That Matters Now

Paul Hawken’s The Ecology of Commerce launched my career in business. By arguing that only business can invent solutions to the environmental destruction wrought by industrial capitalism, he gave people like me a way to make a living and a difference. Hawken set the stage for sustainable apparel start-ups, for new industrialists accelerating our transition toward sustainable energy, for entrepreneurs aiming to end car ownership, for legacy industrialists racing to become the biggest B-Corps, and for a whole new class of social enterprises. It’s happening.

Today, a new form of capitalism threatens to undo that progress. Shoshanna Zuboff has persuasively characterized ours as the era of Surveillance Capitalism, in which we’re creating a crisis in human consciousness through experimentation and manipulation. In her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, she makes a compelling case that the business models of Big Tech driving the surveillance economy must be disrupted in order for our society to continue to thrive.

The underpinning of Surveillance Capitalism is marketing technology. When people say the internet is ad-supported, they mean that marketers like me bankrolled it by investing millions of investor dollars in search, display, social media, and e-commerce. Zuboff’s work raises a question that’s increasingly on the minds of everyone working in tech and unavoidable for marketers: Are we going to be a part of the problem or a part of the solution?

When it comes to privacy and security, Dashlane solves a small part of today’s problems. But it’s addressing real pain points with a transparent business model. Dashlane’s password manager creates a more seamless experience of the web — without requiring you to sacrifice privacy for convenience or ownership for security. An experience that actually brings you closer to people IRL, because you’ll spend less time navigating the walled gardens whose only reason-for-being is keeping you online longer.

We can’t take our digital independence for granted, nor can we expect others to solve this problem for us. We each need to rise to Hawken and Zuboff’s challenge to be part of the solution. That’s why I’m joining Dashlane.

We’re an independent company that represents the interests of the user at login — the moment at which you normally surrender both privacy and security. We’re a culture united around our commitment to these values and driven by a mission to protect them while simplifying life online.

No individual company will solve privacy, just like no one company created industrial capitalism. Instead, many small companies will likely invent new ways of navigating the web, and those that put people at the top of the food chain rather than at the bottom, empowering people to control their own identities online, will win. They’ll increasingly build products to benefit people rather than to collect data about them. They’ll sprout like flowers through the concrete slab of Big Tech’s surveillance economy.

Sign up to receive news and updates about Dashlane